Thinking back on your practice experience, what types of things were dependent on a person’s own truth and more subjective? What types of things would you consider irrefutable truths and more objective?

Last chapter, we reviewed the ethical commitment that social work researchers have to protect the people and communities impacted by their research. Answering the practical questions of harm, conflicts of interest, and other ethical issues will provide clear foundation of what you can and cannot do as part of your research project. In this chapter, we will transition from the real world to the conceptual world. Together, we will discover and explore the theoretical and philosophical foundations of your project. You should complete this chapter with a better sense of how theoretical and philosophical concepts help you answer your working question, and in turn, how theory and philosophy will affect the research project you design.

The single biggest barrier to engaging with philosophy of science, at least according to some of my students, is the word philosophy. I had one student who told me that as soon as that word came up, she tuned out because she thought it was above her head. As we discussed in Chapter 1, some students already feel like research methods is too complex of a topic, and asking them to engage with philosophical concepts within research is like asking them to tap dance while wearing ice skates.

For those students, I would first answer that this chapter is my favorite one to write because it was the most impactful for me to learn during my MSW program. Finding my theoretical and philosophical home was important for me to develop as a clinician and a researcher. Following our advice in Chapter 2, you’ve hopefully chosen a topic that is important to your interests as a social work practitioner, and consider this chapter an opportunity to find your personal roots in addition to revising your working question and designing your research study.

Exploring theoretical and philosophical questions will cause your working question and research project to become clearer. Consider this chapter as something similar to getting a nice outfit for a fancy occasion. You have to try on a lot of different theories and philosophies before you find the one that fits with what you’re going for. There’s no right way to try on clothes, and there’s no one right theory or philosophy for your project. You might find a good fit with the first one you’ve tried on, or it might take a few different outfits. You have to find ideas that make sense together because they fit with how you think about your topic and how you should study it.

As you read this section, try to think about which assumptions feel right for your working question and research project. Which assumptions match what you think and believe about your topic? The goal is not to find the “right” answer, but to develop your conceptual understanding of your research topic by finding the right theoretical and philosophical fit.

In addition to self-discovery, theoretical and philosophical fluency is a skill that social workers must possess in order to engage in social justice work. That’s because theory and philosophy help sharpen your perceptions of the social world. Just as social workers use empirical data to support their work, they also use theoretical and philosophical foundations. More importantly, theory and philosophy help social workers build heuristics that can help identify the fundamental assumptions at the heart of social conflict and social problems. They alert you to the patterns in the underlying assumptions that different people make and how those assumptions shape their worldview, what they view as true, and what they hope to accomplish. In the next section, we will review feminist and other critical perspectives on research, and they should help inform you of how assumptions about research can reinforce existing oppression.

Understanding these deeper structures is a true gift of social work research. Because we acknowledge the usefulness and truth value of multiple philosophies and worldviews contained in this chapter, we can arrive at a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the social world. Methods can be closely associated with particular worldviews or ideologies. There are necessarily philosophical and theoretical aspects to this, and this can be intimidating at times, but it’s important to critically engage with these questions to improve the quality of research.

Although it may not seem like it right now, your project will develop a from a strong connection to previous theoretical and philosophical ideas about your topic. It’s likely you already have some (perhaps unstated) philosophical or theoretical ideas that undergird your thinking on the topic. Moreover, the philosophical questions we review here should inform how you understand different theories and practice modalities in social work, as they deal with the bedrock questions about science and human knowledge.

Before we can dive into philosophy, we need to recall our conversation from Chapter 1 about objective truth and subjective truths. Let’s test your knowledge with a quick example. Is crime on the rise in the United States? A recent Five Thirty Eight article highlights the disparity between historical trends on crime that are at or near their lowest in the thirty years with broad perceptions by the public that crime is on the rise (Koerth & Thomson-DeVeaux, 2020). [1] Social workers skilled at research can marshal objective facts, much like the authors do, to demonstrate that people’s perceptions are not based on a rational interpretation of the world. Of course, that is not where our work ends. Subjective facts might seek to decenter this narrative of ever-increasing crime, deconstruct is racist and oppressive origins, or simply document how that narrative shapes how individuals and communities conceptualize their world.

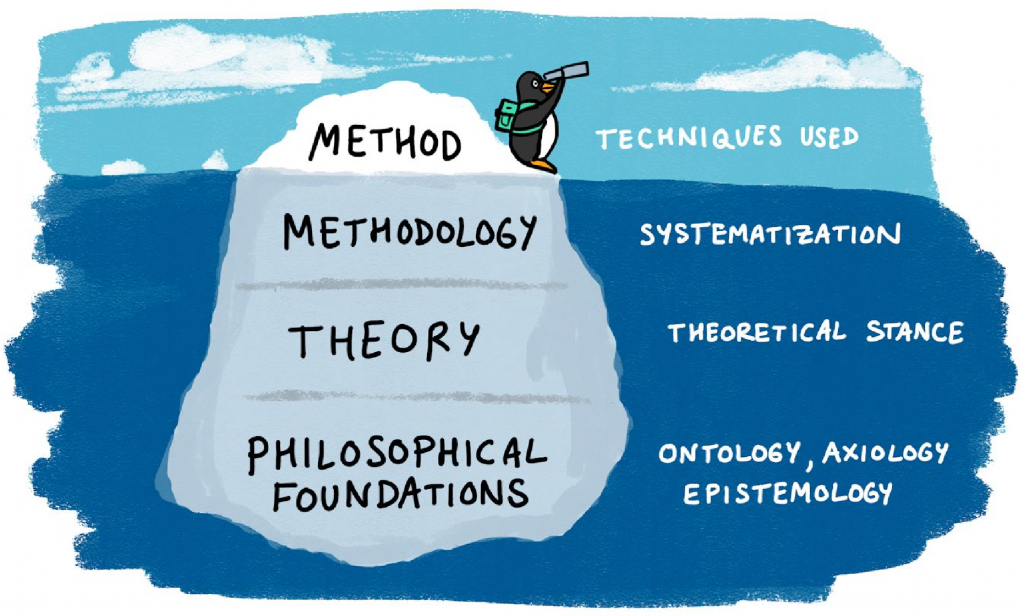

Objective does not mean right, and subjective does not mean wrong. Researchers must understand what kind of truth they are searching for so they can choose a theory(ies), develop a theoretical framework (in quantitative research), select an appropriate methodology, and make sure the research question(s) matches them all. As we discussed in Chapter 1, researchers seeking objective truth (one of the philosophical foundations at the bottom of Figure 5.1) often employ quantitative methods (one of the methods at the top of Figure 5.1). Similarly, researchers seeking subjective truths (again, at the bottom of Figure 5.1) often employ qualitative methods (at the top of Figure 5.1). This chapter is about the connective tissue, and by the time you are done reading, you should have a first draft of a theoretical and philosophical (a.k.a. paradigmatic) framework for your study.

In section 1.2, we reviewed the two types of truth that social work researchers seek—objective truth and subjective truths —and linked these with the methods—quantitative and qualitative—that researchers use to study the world. If those ideas aren’t fresh in your mind, you may want to navigate back to that section for an introduction.

These two types of truth rely on different assumptions about what is real in the social world—i.e., they have a different ontology. Ontology refers to the study of being (literally, it means “rational discourse about being”). In philosophy, basic questions about existence are typically posed as ontological, e.g.:

At first, it may seem silly to question whether the phenomena we encounter in the social world are real. Of course you exist, your thoughts exist, your computer exists, and your friends exist. You can see them with your eyes. This is the ontological framework of realism, which simply means that the concepts we talk about in science exist independent of observation (Burrell & Morgan, 1979). [2] Obviously, when we close our eyes, the universe does not disappear. You may be familiar with the philosophical conundrum: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

The natural sciences, like physics and biology, also generally rely on the assumption of realism. Lone trees falling make a sound. We assume that gravity and the rest of physics are there, even when no one is there to observe them. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful microscope, and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, such as watching an apple fall from a tree. Of course, our theories about gravity have changed over the years. Improvements were made when observations could not be correctly explained using existing theories and new theories emerged that provided a better explanation of the data.

As we discussed in section 1.2, culture-bound syndromes are an excellent example of where you might come to question realism. Of course, from a Western perspective as researchers in the United States, we think that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) classification of mental health disorders is real and that these culture-bound syndromes are aberrations from the norm. But what about if you were a person from Korea experiencing Hwabyeong? Wouldn’t you consider the Western diagnosis of somatization disorder to be incorrect or incomplete? This conflict raises the question–do either Hwabyeong or DSM diagnoses like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) really exist at all…or are they just social constructs that only exist in our minds?

If your answer is “no, they do not exist,” you are adopting the ontology of anti-realism (or relativism), or the idea that social concepts do not exist outside of human thought. Unlike the realists who seek a single, universal truth, the anti-realists perceive a sea of truths, created and shared within a social and cultural context. Unlike objective truth, which is true for all, subjective truths will vary based on who you are observing and the context in which you are observing them. The beliefs, opinions, and preferences of people are actually truths that social scientists measure and describe. Additionally, subjective truths do not exist independent of human observation because they are the product of the human mind. We negotiate what is true in the social world through language, arriving at a consensus and engaging in debate within our socio-cultural context.

These theoretical assumptions should sound familiar if you’ve studied social constructivism or symbolic interactionism in MSW courses, most likely in human behavior in the social environment (HBSE). [3] From an anti-realist perspective, what distinguishes the social sciences from natural sciences is human thought. When we try to conceptualize trauma from an anti-realist perspective, we must pay attention to the feelings, opinions, and stories in people’s minds. In their most radical formulations, anti-realists propose that these feelings and stories are all that truly exist.

What happens when a situation is incorrectly interpreted? Certainly, who is correct about what is a bit subjective. It depends on who you ask. Even if you can determine whether a person is actually incorrect, they think they are right. Thus, what may not be objectively true for everyone is nevertheless true to the individual interpreting the situation. Furthermore, they act on the assumption that they are right. We all do. Much of our behaviors and interactions are a manifestation of our personal subjective truth. In this sense, even incorrect interpretations are truths, even though they are true only to one person or a group of misinformed people. This leads us to question whether the social concepts we think about really exist. For researchers using subjective ontologies, they might only exist in our minds; whereas, researchers who use objective ontologies which assume these concepts exist independent of thought.

How do we resolve this dichotomy? As social workers, we know that often times what appears to be an either/or situation is actually a both/and situation. Let’s take the example of trauma. There is clearly an objective thing called trauma. We can draw out objective facts about trauma and how it interacts with other concepts in the social world such as family relationships and mental health. However, that understanding is always bound within a specific cultural and historical context. Moreover, each person’s individual experience and conceptualization of trauma is also true. Much like a client who tells you their truth through their stories and reflections, when a participant in a research study tells you what their trauma means to them, it is real even though only they experience and know it that way. By using both objective and subjective analytic lenses, we can explore different aspects of trauma—what it means to everyone, always, everywhere, and what is means to one person or group of people, in a specific place and time.

Having discussed what is true, we can proceed to the next natural question—how can we come to know what is real and true? This is epistemology. Epistemology is derived from the Ancient Greek epistēmē which refers to systematic or reliable knowledge (as opposed to doxa, or “belief”). Basically, it means “rational discourse about knowledge,” and the focus is the study of knowledge and methods used to generate knowledge. Epistemology has a history as long as philosophy, and lies at the foundation of both scientific and philosophical knowledge.

Epistemological questions include:

While these philosophical questions can seem far removed from real-world interaction, thinking about these kinds of questions in the context of research helps you target your inquiry by informing your methods and helping you revise your working question. Epistemology is closely connected to method as they are both concerned with how to create and validate knowledge. Research methods are essentially epistemologies – by following a certain process we support our claim to know about the things we have been researching. Inappropriate or poorly followed methods can undermine claims to have produced new knowledge or discovered a new truth. This can have implications for future studies that build on the data and/or conceptual framework used.

Research methods can be thought of as essentially stripped down, purpose-specific epistemologies. The knowledge claims that underlie the results of surveys, focus groups, and other common research designs ultimately rest on epistemological assumptions of their methods. Focus groups and other qualitative methods usually rely on subjective epistemological (and ontological) assumptions. Surveys and other quantitative methods usually rely on objective epistemological assumptions. These epistemological assumptions often entail congruent subjective or objective ontological assumptions about the ultimate questions about reality.

One key consideration here is the status of ‘truth’ within a particular epistemology or research method. If, for instance, some approaches emphasize subjective knowledge and deny the possibility of an objective truth, what does this mean for choosing a research method?

We began to answer this question in Chapter 1 when we described the scientific method and objective and subjective truths. Epistemological subjectivism focuses on what people think and feel about a situation, while epistemological objectivism focuses on objective facts irrelevant to our interpretation of a situation (Lin, 2015). [4]

While there are many important questions about epistemology to ask (e.g., “How can I be sure of what I know?” or “What can I not know?” see Willis, 2007 [5] for more), from a pragmatic perspective most relevant epistemological question in the social sciences is whether truth is better accessed using numerical data or words and performances. Generally, scientists approaching research with an objective epistemology (and realist ontology) will use quantitative methods to arrive at scientific truth. Quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world. For example, while people can have different definitions for poverty, an objective measurement such as an annual income of “less than $25,100 for a family of four” provides a precise measurement that can be compared to incomes from all other people in any society from any time period, and refers to real quantities of money that exist in the world. Mathematical relationships are uniquely useful in that they allow comparisons across individuals as well as time and space. In this book, we will review the most common designs used in quantitative research: surveys and experiments. These types of studies usually rely on the epistemological assumption that mathematics can represent the phenomena and relationships we observe in the social world.

Although mathematical relationships are useful, they are limited in what they can tell you. While you can use quantitative methods to measure individuals’ experiences and thought processes, you will miss the story behind the numbers. To analyze stories scientifically, we need to examine their expression in interviews, journal entries, performances, and other cultural artifacts using qualitative methods. Because social science studies human interaction and the reality we all create and share in our heads, subjectivists focus on language and other ways we communicate our inner experience. Qualitative methods allow us to scientifically investigate language and other forms of expression—to pursue research questions that explore the words people write and speak. This is consistent with epistemological subjectivism’s focus on individual and shared experiences, interpretations, and stories.

It is important to note that qualitative methods are entirely compatible with seeking objective truth. Approaching qualitative analysis with a more objective perspective, we look simply at what was said and examine its surface-level meaning. If a person says they brought their kids to school that day, then that is what is true. A researcher seeking subjective truth may focus on how the person says the words—their tone of voice, facial expressions, metaphors, and so forth. By focusing on these things, the researcher can understand what it meant to the person to say they dropped their kids off at school. Perhaps in describing dropping their children off at school, the person thought of their parents doing the same thing. In this way, subjective truths are deeper, more personalized, and difficult to generalize.

As you might guess by the structure of the next two parts of this textbook, the distinction between quantitative and qualitative is important. Because of the distinct philosophical assumptions of objectivity and subjectivity, it will inform how you define the concepts in your research question, how you measure them, and how you gather and interpret your raw data. You certainly do not need to have a final answer right now! But stop for a minute and think about which approach feels right so far. In the next section, we will consider another set of philosophical assumptions that relate to ethics and the role of research in achieving social justice.

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Does an objective or subjective epistemological/ontological framework make the most sense for your research project?

Using your answer to the above question, describe how either quantitative or qualitative methods make the most sense for your project.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching bullying among school-aged children, and how this impacts students’ academic success.

a single truth, observed without bias, that is universally applicable

× Close definitionone truth among many, bound within a social and cultural context

× Close definitionassumptions about what is real and true

× Close definitionassumptions about how we come to know what is real and true

× Close definitionquantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world

× Close definitionqualitative methods interpret language and behavior to understand the world from the perspectives of other people

× Close definitionDoctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.